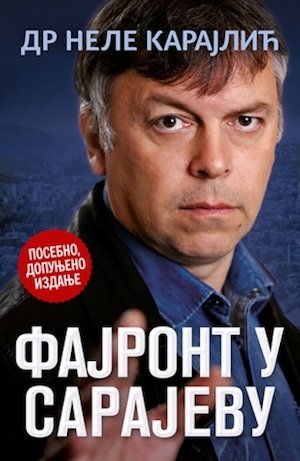

Fajront u Sarajevu

Dr Nele Karajlić

Laguna, 2015

Often when people hear the name “Yugoslavia,” they recognize it because of the war, or wars, of the 1990s. Another case of Communism, of ethnic and religious hate, of destruction. So much so that even I, a product and curious child of ex-Yugoslavia, fell into the narrative, got sucked into the war whirlpool of the ’90s, forgot there ever existed a before, focused only on the pain and on the after. I always assumed I knew why the war happened, but I didn’t realize I was missing so much everyday context. I didn’t know Yugoslavia could be beautiful because I only ever knew it as tragic.

Enter Fajront u Sarajevu (Closing Time in Sarajevo), a memoir written by Dr Nele Karajlić (whose actual name is Nenad Janković, but he’s more known for and uses his stage name), outlining his experiences through the 1980s and into the 1990s. He introduces a history I had never known, and learning it rattled me because this new history, I realized, is as much mine as it is his. All of the events that took place in Dr Nele Karajlić’s life inevitably, and however indirectly, led to me and my life.

So who is Dr Nele Karajlić? What’s he done? Why should we care? Prior to reading his memoir, I mainly only knew him for one thing: his participation in Tata’s (my dad’s) favorite rock band, Zabranjeno Pušenje (No Smoking), in its original iteration. I also knew, very peripherally, that he had some sort of radio-turned-television show Tata said was so good and raw that it predicted the ’90s conflicts. I didn’t pay much attention to this. My born-in-1997, immigrated-to-America-in-the-early-2000s self connected with and cared for the music. Ex-Yu rock became my best friend in the foreign world I was in. This music helped me make sense of heartbreak, angst, displacement, discrimination, war, and love. Zabranjeno Pušenje songs weren’t the guiding anthems of my youth; they were always there, and I listened to them with Tata or with friends, but I wasn’t ready to make sense of them yet. Even then, I knew theirs was a distinct sound, feeling, purpose. Only recently, and definitely after reading the memoir, did I begin to listen with a ready ear. Karajlić was the frontman of the original Zabranjeno Pušenje, active mainly in the 1980s and into the 90s. He was also one of the leaders of the New Primitivism movement started in Sarajevo around 1983. He is an actor and one of the creators of the radio-turned-television series Top Lista Nadrealista (Top List of Surrealists). He’s a musician, writer, comedian, director, husband, and father. And he’s Serbian, a very important fact to mention, important because of this region’s history.

All my life, ex-Yu rock was there for me, but for whatever reason, it was separate, in my mind, from the war. I didn’t associate the music I loved with the war because I hadn’t understood the influence of the prewar period and how the artistry of that period was a result of a certain kind of unrealized pressure, how the pressure had to cause destruction at some point, in some way. In our case, in Yugoslavia, it was in the very worst way. Fajront u Sarajevu depicts the pre-war world in such delicate yet raw aspects—Karajlić shows us his band’s talent and growth; he shows us the sub-cultural movement that was clearly a rebellion led by kids in their 20s before they even realized what was happening around them; he shows us the confusion and tension Josip Broz Tito’s state instilled in its multi-ethnic citizens; he shows us the fear and how quickly an entire country crumbles because someone somewhere needs a war; he shows how the music, the scriptwriting, and the acting were a genuine response to the silent chaos of 1980s Yugoslavia; he shows us how this generation’s art was ignored, and as a result, many of that generation, and generations following it, died or had to flee, some confused and shocked, all reeling from the aftermaths of war. Karajlić’s memoir isn’t the only one, and it doesn’t speak for everyone; however, it’s an ode to those voices that were lost and then had to emerge from the rubble.

To begin his memoir, Karajlić employs a unique and seemingly fictional framing by introducing the first two characters—Madam Fate and Archangel Azrael. They’re sitting in a bar café, discussing their jobs, trying to figure out who they’re both waiting for. Archangel Azrael, commonly referred to as the Angel of Death, is a disheveled, chain-smoking alcoholic just doing his job, taking souls to their next destination. Madam Fate, a wise, patient lady, is in charge of human lives, i.e., their fates. In the opening scenes, Madam Fate is trying to understand from Azrael who he’s waiting for and why she’s been sent to this place. They compare notes and realize they’re both waiting for Dr Nele Karajlić, at which point Karajlić introduces a third character, a human, the one Fate and Azrael have been waiting for, Karajlić himself.

We watch Karajlić go about his routine as Fate and Azrael discuss their offices’ miscommunication; Fate tells Azrael he shouldn’t be there because Karajlić still had many years of life left. They argue, they get angry, and they watch as Karajlić develops chest pain while getting in his car, tries to wait it out, but it gets so bad that he asks a passerby for directions to the ER, and somehow drives himself to the doors. A medical emergency unfolds, panic, pain, Karajlić’s disoriented thoughts, and finally, an ambulance to take the patient to a better-equipped hospital. The patient is loaded in with one medic in the back, and off they go to Beograd, lights on. Karajlić opens his eyes—they’ve managed to stabilize him—and he sees he’s in the company of the two characters he saw earlier in the bar café, Madam Fate and Archangel Azrael. The three of them begin to talk, and Azrael’s impatience wears thin as he waits for this human to die and demands, at the very least, a story. Fate won’t let death happen but wants to hear Karajlić talk about his life. And so Karajlić begins.

The tension and comedic relief Karajlić employs in these opening scenes work beautifully to engage us as readers and give us a sense of urgency, for the patient in this story is a well-known celebrity, someone we already care deeply about. Karajlić, throughout the book, goes back and forth from the ambulance to stories from his past. The two threads are woven together and work well, even though the transitions can sometimes be abrupt. Nonetheless, we enter Karajlić’s intimate thoughts and feelings, and we listen as he takes us through his life. And just when we begin to immerse ourselves entirely in his past, he brings us back to the speeding ambulance and eventually the hospital, to the banter he shares with Madam Fate and Archangel Azrael. There are scenes where the three of them talk about how death works, or about free will, and these deeply philosophical yet colloquial moments amplify the stories that surround these conversations. We’re reminded he’s fighting a massive heart attack to stay alive the whole time he’s telling us his survival story, how he lived through the tensions of the 80s and the war of the 90s.

And just as soon as we’re pulled into the ambulance, we’re back in 1985, watching Karajlić and his band deal with their sudden notoriety for allegedly spreading hate about Tito, the president of Yugoslavia who died in 1980. Karajlić and the band were blacklisted, questioned by the authorities, lost most of their popularity, and the government even took Karajlić to court. It was a bleak future for anyone the Communist state found problematic. What’s most interesting in this situation, as Karajlić points out, is that Tito’s Yugoslavian narrative had been so enforced that even five years after his death, when the façade slowly began to fade, people remained terrified, and they remained in denial. Karajlić very deliberately, as he continues to write, shows us how his generation’s entire belief system started coming apart at the seams. They were all raised as Yugoslavians, and they were proud to identify as such, so when tensions rose even more, they were confused as they were split up into Croatians, Bosnians, and Serbians. Karajlić writes, about his band: “One of us is Croatian, one Bosnian Muslim, and the third a Serb . . . It was so natural for us. We grew up that way. I remember, one interviewer asked us what nationality we were. All three of us said Yugoslavian. He just laughed. ‘Ok, sure, Yugoslavian, but what are your nationalities?’ So much for Yugoslavia” (255).

Fajront u Sarajevu is an unveiling—at least it is for me. There was so much I didn’t understand, and still don’t, about Yugoslavia and the war. History books only teach us so much. The artifacts and the voices behind those artifacts—that’s where we can gain more genuine insights. Zabranjeno Pušenje’s songs, Top Lista Nadrealista episodes, and this memoir remind us that what’s beautiful was there all along, but as is often the case, the tragedy overshadows the friendships, the moments in the basement as the band practices, the concerts, the laughter, the camaraderie, the love. Because of this inevitable fact, people of my generation who have inherited so many narratives of war have lost so much. We’ve grown up without a lot of emphasis on or room for nuance and objectivity. I’ve had countless experiences in my life that have made me wonder what I did to incite such dislike in someone who comes from the same place as me. The obvious and easy answer is the war, and so we keep our distance, each stuck villainizing the other. But what we fail to understand, what Karajlić shows us, is that we are capable of more than what the system shoves at us or makes us believe. Perhaps that’s why Karajlić wrote this book. In any case, he’s gifted us not with a way forward, not with a solution, but with a history that is more than war, than hate, than tragedy. A history I am proud is mine.

Milica Mijatović

Milica is a Serbian poet and translator. Born in Brčko, Bosnia and Hercegovina, she relocated to the United States where she earned a BA in Creative Writing and English Literature from Capital University. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Boston University and is a recipient of a Robert Pinsky Global Fellowship in Poetry. Her poetry appears or is forthcoming in Rattle, The Louisville Review, Poet Lore, Collateral, Santa Clara Review, Barely South Review, and elsewhere.