Translator’s Note: “How We Spent the Fifties” is a satirical short story from a collection of humorous stories written by Miloslav Šimek and Jiří Grossmann that tells the tale of the turmoil and absurdity of a family that’s bending over backwards in support for the communist party. It was written for all those who appreciate humour and laughter in response to the communist oppression in Czechoslovakia and demonstrates how humour was used as a tool to prevail during those difficult times.

The aim of this translation is to bring Šimek and Grossmann’s work to a more varied readership, while maintaining a high degree of faithfulness to the source text, Czech culture, and humor in order to ensure that the cultural atmosphere of the time and place come alive. The humor relies on wordplay, using words and phrases with many references to the history of Czechoslovakia, its people, and their customs. The language and register as well as the style reflect the expressions and colloquialisms that would have been commonplace in Czechoslovakia in the 1950s. However, by exaggerating the formality of the tone and language the authors thereby add to the humour and irony of the text.

Following the tradition of Czech humour exemplified in the writings of Jaroslav Hašek, Karel Čapek, and Zdeněk Jirotka, the tales of the vagaries of life by Šimek and Grossmann are considered Czech classics. “How We Spent the Fifties” provides the reader with an opportunity to explore the cultural relevance of the Russian Communist influence on the relationship between the Czech and Russian cultures. It also gives the reader an insight into the coping mechanisms necessary for the people to survive the hardships of the era.

Because of censorship in Czechoslovakia at the time, many of Šimek and Grossmann’s stories could not be published as political satire or caricatures of national leaders were not allowed. This is why the collection of short stories including “How We Spent the Fifties” was only published as a book decades later in 1993.

Despite the continued popularity of the short stories since circulating within the context of theatrical performances by the authors, they were never translated into any other language. This is mainly due to the difficulties that arise when translating the text, in particular the usage of linguistic, stylistic, and cultural particularities of the Czech humour.

For example, Šimek and Grossmann’s choice of personal names in their work is deliberate, and intended to contribute to the overall humor of the text. Although I am aware that the preservation of the Czech names might feel more alien to the English reader due to their linguistic form and non-familiarity, their preservation fulfills the skopos of the translation—i.e., they maintain a high degree of faithfulness to the source text and the Czech culture and humor.

Although written more than fifty years ago, Šimek and Grossmann’s stories remain incredibly popular and appeal not only to those who lived through the communist regime but also to younger generations. Even though their stories are extremely well-known, their phrases have become so integrated into Czech culture that on occasion, those who use the phrases are unaware of their origin. They are ingrained in the culture to such an extent that you hear them on a daily basis, often used in situations that reflect their original use in the stories—e.g., on a crowded public transport or in shops and cafes.

When I interviewed Mrs. Magdaléna Šimková, she stated that the greatest accolade for her late husband would be the fact that many phrases and terms from his work have become commonplace in both Czech Language and culture.

![]()

Human history can be divided into the following periods: prehistory, antiquity, the Middle Ages, the modern age, and the 1950s, also known as the Cult of Personality Period. Although much has been written regarding the last period, a significant part of our family history is yet to be completely understood. Briefly, I will recount my memories.

In our family, all the roles were distributed equally. My mother worked. My sister worked. My brother worked, and I worked like a packhorse. Meanwhile, my father, an official in the Communist Party, fed us all. True, we were well-fed. Sometimes, we could even indulge in lentils and wash down our Sunday dinner’s grease with beer. However, he did expect a lot in return.

Every week, he checked our Trade Union and Pioneer identity cards punishing us with twenty squats for missing stamps, and any creasing of the corners was accompanied by a grunt of discontent.

My father liked it when the family stood at the forefront of progress. Even on April 30th, he would make sure we were prepared for the May Day parade by rehearsing the route and practicing cheerful expressions on our faces. On Marx’s birthday, we would always read a randomly selected passage from Das Kapital and then have some cake. Those who didn’t read fluently would lose their icing.

Once, before Easter, my father received an unexpectedly thick letter from the United States. He turned crimson with embarrassment and said, “What’s that supposed to mean? This could damage my unblemished reputation, and all my hard work will have been wasted!” He picked up the weighty letter with an air of disgust, disinfected it with vodka, and, gnawing on a blini, cut the envelope open with a Cossack saber.

Then he started to read. Suddenly, he went pale and slid to the floor. As though he had been chopped down, he fell onto the mosaic of political magazines, which we had on the floor instead of a carpet. Resuscitation started. We sprinkled Father with petroleum and gave him a whiff of some taiga herbs our auntie had sent us from Novosibirsk. Father awoke from the swoon and ordered Mother to fetch the samovar.

“Sadites!” he uttered, still pale. “Imagine, Comrades sons and daughters, that we inherited $100,000 and a fifth of the Ford company’s stock.” Father started to weep and whimper, “Svoloch amerikanskaia!”

“Hurray!” cried my brother Ivan. “We can buy a Czech car and maybe even have some money left!”

“Well, well, well,” cried my father. “Who but you would accept a cursed groschen from the West? All it takes is to offer you some lolly and they got you hooked! I’m very well aware that you and that reactionary crony Kokořín are bedfellows.” He continued, “Once, when I went to check the notice board in your room, which is the reflection of your political activity, I distinctly smelled that ‘booble gum!’ I wasn’t going to mention it. However, after today’s antics, I have no option but to ask you to go and copy out the Communist Manifesto five times.” My brother obediently sharpened his pencil.

“Any more suggestions about the letter?” Father encouraged us triumphantly.

“Vile!” yelled sister Anna sycophantically. “I would burn the damned letter!”

“Excellent,” My father praised her. “Here’s five Crowns. Treat yourself to some borsch by the Powder Tower.”

At that moment, my mother whispered timidly. “You know Václav Václavovich, the capitalist is wicked, disgusting even, but $100,000 is a lump sum. There are a few things we need, and as the Alexandrov Ensemble is arriving this month, you’ll want to be at the front in your best bib and tucker.”

“Et tu, Marusia?” Father called out desperately, carving the caricature of Adenauer nervously on the table to regain his composure.

“Anyway, who actually left us this paltry sum of money?” I chimed in.

“You don’t want to know, son,” Father bawled. “It was your uncle, my brother, who has disgraced us. Since he accidentally dug down forty feet from the Macocha Abyss to Austria and looked up to capitalists, the only thing we’ve exchanged were curses. And he does this to destroy me. But I won’t touch the filthy lucre. In the next public meeting, I will clear my name, open the hearts of Comrades, and I will pull my socks up for the party.”

The bell rang. Father tucked the letter under his shirt and spread some halva around his mouth. Then he went to open the door. In came Comrade Dyba, a member of the party, accompanied by others.

“To what do I owe the pleasure?” asked my father nervously, clutching his shirt.

“We’re here regarding a letter from the United States,” said Comrade Dyba coldly, glancing at the library to make sure the busts were all in place.

“My friends, I’m innocent,” Father muttered. “Of course, I’d never accept any money; I have witnesses!”

“Although these dollars are filthy, the capitalist must be deprived of them, you see, so he can learn what poverty is like,” said Dyba.

“So that’s solved then,” My mother interjected. “Who should we give it to?”

“Madame Comrade reasons well,” Dyba praised her. “You have a charming and understanding wife, Václav Václavovich. Have her bring the money to me.”

*

And that’s how we came to live alone with our father. Over time, many things have changed, and even Father realized that nothing lasts forever.

Nowadays, he has plenty of time to ponder as he sweeps Neruda Street from dawn to dusk.

He is fond of his job and faithfully obeys the rules signed by Comrade Dyba at the Ministry.

Miloslav Šimek and Jiří Grossmann (Authors) / Jakub Böhm (Translator)

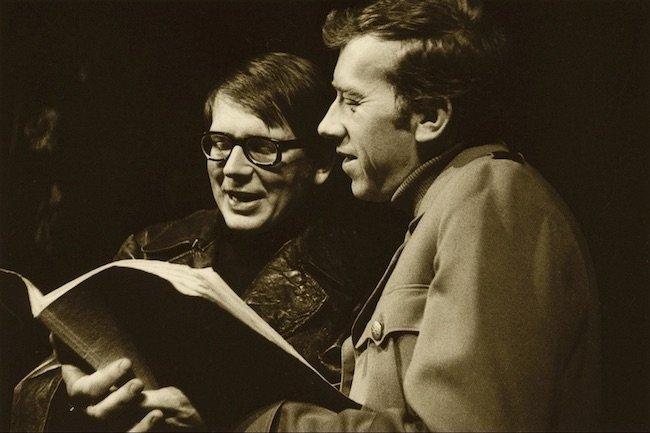

Miloslav (1940–2004) and Jiří (1941–1971) left their careers to establish a humorous duo-act writing poetry, short stories and plays. They were best known as the authors of satirical short stories describing how family life, school, and society played out during the Communist oppression in Czechoslovakia. Their open disapproval of the regime lead to their persecution during the Soviet occupation.

Jakub was born in Ústí nad Labem, Czech Republic. He holds a BA degree in English Language for Education and an MA in Translation and Interpreting Studies from The University of Manchester. Currently, he is seeking publishers for a collection of satirical short stories by Miloslav Šimek and Jiří Grossmann.