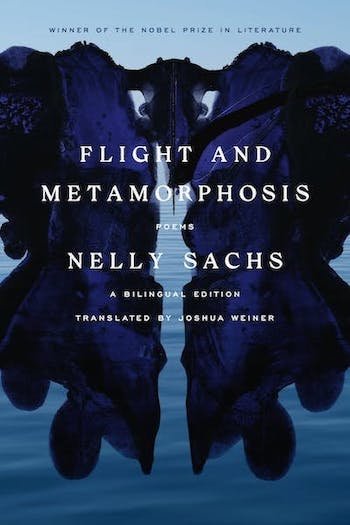

Flight and Metamorphosis: Poems

Nelly Sachs

Translated by Joshua Weiner with Linda B. Parshall

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022

Although I am usually wary of presentism, the too-easy application of historical situations to current contexts, I find that Joshua Weiner’s new translation of Nelly Sachs’ 1959 Flucht und Verwandlung is a book I can lean into in this time of global crises. As a researcher trained in German Studies, I know the trajectory of Sachs’ work from her best-known Holocaust poems (“O the chimneys” from 1947 among them) to more cryptic writings during her postwar exile, and until now I’ve considered her dramatic language necessary and belonging to its time. Yet this side-by-side edition of Flight and Metamorphosis, to which Weiner brings deep knowledge of both poetry and migration studies, has surprised me. It builds in a crescendo of trauma-inflected song that not only speaks from Sachs’ own postwar processing but also presses forward into our time as “those who come after,” to quote Brecht’s phrase from 1939. These poems, and their renderings in incisive, sometimes explosive English, do not generalize but generate sounds and images that model the stakes for contemporary poetry, too. As the climate crisis becomes more and more palpable, intensified by war and injustice in the human sphere and affecting countless species outside it, “poetry of witness” does need the level of prophetic force that Sachs’ words enact.

During her thirty-year exile in Sweden, the Nobel Prize-winning poet of the Shoah left behind her more descriptive work of the 1940s in favor of image-kernels that reflect Judaic ideas of tikkun olam, framed in Rabbi Isaac Luria’s kabbalistic terms as the divine scattered in pieces and in need of repair. Unlike her friend Paul Celan, who wished to “blaspheme till the end” in his own cracked-open German, Sachs allowed received words to speak for themselves, linked with prepositions and genitives, cryptic mainly in word choice. Her occasional neologisms (“Feuergesetz” or “law of fire,” for example) are less shocking than Celan’s intentionally forced compounds, though both poets’ works exploit the puzzle-like logic of German. In Weiner’s translations, Sachs’s alliteration and internal and slant rhymes occur at different points in each stanza but carry the source texts’ weight in letting nouns and noun phrases do most of the work. Some haunt me long after reading: “night-lava,” “century’s rut,” “sea-glyph,” “the fly’s inscription,” “your body’s secret cord.”

Sachs’ poems read on two levels, the earth-rooted and the cosmic. The resonance of war and genocide spills through closely woven lines, making them ring and shine. This occurs not only through the language itself but also through what Axel Englund has described as its sonic infrastructure, mirroring the music of the cosmos or “musica mundana, which organizes the universe but which, in Sachs’s interpretation, has been profoundly disturbed by earthly terror.” Explicit musical references in Flight and Metamorphosis enliven stones, the sea, a dying star, and Aeolian-harp sounds of wind in the leaves. The world itself seems to be alive with sound voicing past trauma and warning of future apocalypse; if, “in a smokecloud of error / we have / created a wandering cosmos / with the language of our breath” . . . “still we work your field / behind death’s back.” Like a repeated musical phrase, a word can return again and again, like a pulse or a siren through the entire collection. Weiner collects Sachs’s repeated keywords in his Introduction: “night, nothing, breath, wind, body, seed, kernel, sand, grain, dust, vein, cord, light, flash, spark, fire, meteor, constellation, refuge, dwelling, possession, longing, rose, blossom, compass, departure, eternity, scream, cry, pain, flight, boundary, land, homeland.” This repetition links past and future, the individual body and the planet itself—longing for “rest on the flight” and yet ready to burst. Sachs’ poems reach into a post-anthropocentric future, as she imagines sounds no human will hear: “and / from a dying star / music will sound / not for the ear”; “How much sleeping music / in the wooded thicket / where the wind, / all alone, / plays the midwife.”

Weiner’s translations achieve that rare balance of closeness to the source text’s intent and vivid presence in English. Early in the book, the prophetic “Who dies” (the poems titled by first lines throughout) moves from German syntax, with lines weighted toward their end verbs, to oracular future tense in English. This more declarative poem retains the solemnity of its source, which envisions a frightening future of blood, lightning, and flooded shoes, Noah’s ark long gone down “star-figured avenues.” The English rendering does lose some implicit references (“stigmatisieren,” which includes both “stigmatize” and “stigmata,” becomes “branding”), but in a move that makes the translation as hard to forget as the German text, Weiner creates his own new word for a fish’s dorsal fin, the “backsail” that “draws back dissolving time / into its tomb.” Sachs’s pairing of “Rückenflosse Heimwehsegel” would sound awkward as “dorsal fin homesickness-sail” and draw the reader out of the poem; “homesick backsail” keeps the two-way journey in motion, between source and adaptation and between dark memory and the floods to come.

When I first read this collection several months ago, I jumped to the idea that an ecocritical reading of Flight and Metamorphosis would miss the point. Certainly the anticipatory grief of climate catastrophe is not the same as collective mourning after genocide. At the same time, one poet’s historical awareness can move through her work toward a time of unanticipated suffering, without reducing either or conflating both. These poems are not only remembrances and prophecies of doom, however. Late in the book, the image of rising “coal forests” calls the reader to attention, to the memory of humans splitting fire from its bed in the earth, and to a wish for return to “the mothers / of the waves.” We know the damage our rogue species can do, on a human and a planetary scale; we need poetry that both names our exile and calls us home.

* * *

Sources

Englund, Axel, “Cosmos and corporeality: notes on music in Sachs’s poetry,” in Nelly Sachs im Kontext: Eine ‘Schwester Kafkas’?, edited by Florian Strob and Charlie Louth, Universitätsverlag Winter, 2014, 51-72.

Heidi Hart

Heidi is an Art and Humanities Research Fellow with SixtyEight Art Institute in Copenhagen, and she also serves as a Nonresident Senior Research Fellow in the Environment and Climate program of the European Center for Populism Studies. She holds an M.F.A. from Sarah Lawrence College and a Ph.D. in German Studies from Duke University. She completed a postdoc at Utah State University and is a regular guest instructor at Linnaeus University in Sweden. She has received an ACLS-Mellon fellowship, several grants for environmental arts and curriculum development, and a Pushcart Prize for poetry. Her publications include the literary memoir Grace Notes (University of Utah Press, 2004), the quartet-series poetry collection Edge by Edge (Toadlily Press, 2007), and two academic monographs, Hanns Eisler’s Art Songs: Arguing with Beauty (Camden House, 2018) and Music and the Environment in Dystopian Narrative: Sounding the Disaster (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), as well as numerous literary and critical essays. Her curatorial work includes Climate Thanatology, an international arts constellation on music and climate grief, with a related book forthcoming from Really Simple Syndication Press.