President

Directed by: Camilla Nielsson

Release Date: 2021

How bad was life in Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe, the brutal kleptocrat who held power in that sorrowful nation for almost forty years? This bad: When the British mercenary Simon Mann tried to break out of Zimbabwe’s infamous Chikurubi prison in 2007, he had a series of guards whispering in his ear, asking if he would please take them with him. Few countries suffer under a legacy of violence and political suppression as extreme as Zimbabwe’s, beginning with decades of war and civil strife to overthrow the white minority regime of its colonial era, followed by additional decades of corruption under the government that subsequently took power after independence. As a result, Zimbabwe is a case study in the difficulty of establishing a functional democracy in a place so battered and traumatized by war.

When Mugabe was finally removed from office in 2017, he was succeeded by his own vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, who had led the putsch against him. A year later, Zimbabwe was poised to hold an election to decide its next president, with Mnangagwa facing off against the opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). But less than four months before election day, Tsvangirai died of cancer, leaving a forty-year-old Stanford-educated attorney and party official named Nelson Chamisa as the MDC’s candidate.

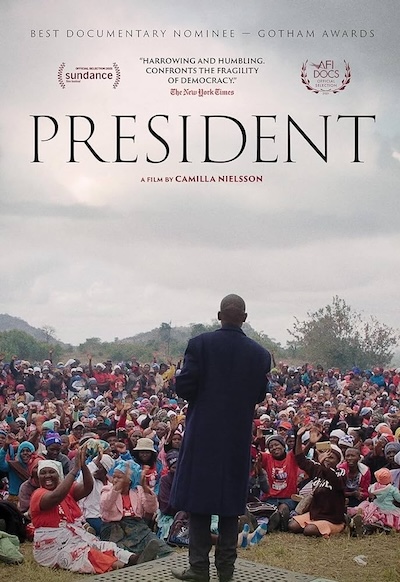

The Danish filmmaker Camilla Nielsson’s 2021 documentary President is a gripping account of that election. Firmly in the vérité tradition, eschewing talking heads and narration for a purely observational approach (save for a few title cards in the interest of economy), its lean account of the campaign, distinguished by astounding access to Chamisa and his inner circle, tells a riveting tale—and a cautionary one—about how elections are stolen in the modern era.

Were Nielsson’s documentary a Hollywood film, surely someone would complain that the casting is too absurdly on-the-nose. Handsome, charismatic, and eloquent, Nelson Chamisa is full of gravitas, intelligence, and integrity, inspiring rock star-like adulation from a Zimbabwean public that sees him as its only hope for ending decades of corruption. Initially dismissed as too young, he quickly proves to be a transformational politician. (Nielsson shows us BBC file footage from 2007 of him after being beaten nearly to death by goons from Mnangagwa’s party, the Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front, or ZANU-PF.) MDC’s signature gesture is the “open hand,” held aloft to represent honesty and transparency. “Show me your hands!” Chamisa cries out to his adoring campaign crowds, who respond with arms held high and palms forward, a stirring visual representation of a political ideal.

Meanwhile, Mnangagwa oozes menace as he assures the international press that his government will conduct a “free, fair, and credible election.” Asked if he will abide by the result, Mnangagwa swears that he will—an easy promise to make, because he knows that he controls that process and will personally determine the winner.

Mugabe himself had come to power by democratic means, winning the prime ministership in a landslide in 1980 ahead of the country’s emancipation from the UK. But under his leadership, ZANU-PF had a long tradition of rigging elections, including those in 2002 and 2008, which pitted him against Tsvangirai. It is clear in the film that Mnangagwa intends to use the same strategy.

ZEC—the Zimbabwean Election Commission—which is responsible for overseeing the election and counting the vote, proves to be a shameless tool of the regime, even as Mnangagwa’s ministers insist they have no control over it, a claim that Nielsson’s film convincingly exposes as risible. We see ZEC begin printing ballots without MDC’s participation, and denying the opposition access to the voter rolls. In a country roiled with hunger, ZANU-PF also distributes food at its rallies in exchange for votes, and threatens to cut off that sustenance if support wavers.

Just two weeks before voters go to the polls, Chamisa threatens to pull out of the race over these and other howling irregularities. But he and his advisors soon realize that ZEC is deliberately trying to provoke that very response. So Chamisa stays in the race, betting that he can still prevail, and counting on an overwhelming numerical victory that would be impossible to deny. But he and his team vastly underestimate Mnangagwa’s willingness to commit the electoral equivalent of armed robbery in broad daylight and get away with it.

When election day finally comes, turnout and passion are on Chamisa’s side. As the MDC tallies the numbers and sees that it has definitively won, ZEC delays releasing any official results, an ominous sign. As the vote count carries on behind closed doors, with only ZANU-PF allowed access to the process, the MDC’s offices are raided by the police, its computers seized, and its staffers arrested. Chamisa himself is forced into hiding due to death threats. Almost inevitably, Nielsson’s film loses some steam once he is off camera, which is the case for much of its final act. Perhaps ironically from a narrative standpoint, removal of the key opposition leader was of course critical to ZANU-PF’s broader strategy.

When angry Zimbabweans spill into the streets, Nielsson films the violence as the army puts down the protests via truncheon and gunfire, killing six and wounding many more. Her matter-of-fact documentation of that brutality is executed with the same lack of sensationalism as the rest of the film, such that it gives the lie to ZANU-PF’s subsequent attempts to downplay the violence, effectively circumventing any need for heavy-handed editorializing by the filmmaker.

After several days of highly suspicious delay, ZEC declares Mnangagwa the winner by a scant thirty-two thousand votes—a brazen theft with only the thinnest veneer of legality. Chamisa and the MDC denounce the process as rigged and the case eventually winds up in the Zimbabwean Supreme Court, where the justices announce that MDC has not produced any evidence of fraud, thereby affirming Mnangagwa’s victory. Without being explicit about the extent to which the Court—like ZEC—is or is not controlled by ZANU-PF, Nielsson leaves us with the distinct impression that all of Zimbabwe’s political institutions are under the thumb of the regime.

According to my survey of the major outlets, western coverage of the election largely bought into the ZANU-PF narrative. The BBC announced Mnangagwa’s victory in anodyne, unquestioning terms, noting only that “The chairman of Mr. Chamisa’s MDC Alliance said the count could not be verified.” Even The Guardian reported that Mnangagwa “has won the country’s historic and hotly contested presidential election,” acknowledging the intensity of the electoral contest, but stating the ZEC’s official, rigged numbers without comment. It then quoted (and reprinted, in an enormous color illustration) Mnangagwa’s victory tweet stating that he was “humbled to be elected President,” and that “This is a new beginning. Let us join hands, in peace, unity & love, & together build a new Zimbabwe for all!” Though The Guardian did in passing mention his implication in Mugabe’s crimes and the killing of protestors, the paper didn’t note any allegations of fraud until the sixth paragraph, and then only in a manner that gave little credence to the complaints. An article in The New York Times took at face value the Zimbabwean Supreme Court’s subsequent decision affirming Mnangagwa’s win (though its editorial board railed against it), writing that “international and domestic observers . . . described the election campaign as free and peaceful,” and “not marred by the widespread fraud alleged by the opposition.”

The yawning disconnect between the depiction of the election presented in President and that offered by the mainstream media is highly instructive. Of course, perspectives can be wildly different, but the depth of detail in Nielsson’s film, its up-close-and-personal access, and the length of time it spends with the pertinent players, lend it a strong advantage in terms of the relative credibility of these divergent accounts.

For a Westerner audience member, it is all but impossible to view President without considering how perfectly Mnangagwa’s attempt to hold on to power in Zimbabwe in 2018 presaged Trump’s attempt to do the same in the US two years later. As we observe how uncritically the mainstream media accepted the ZANU-PF narrative, Camilla Nielsson’s remarkable film also serves as a sterling example of how journalists and documentarians on the ground can provide a stark informational antidote to a narrative that autocracies would otherwise readily impose.

Chamisa is expected to challenge Mnangagwa again in July 2023. In parliamentary races this past March, his party—now under the banner of the Citizens’ Coalition for Change—won a resounding nineteen of twenty-eight seats in the national assembly even as ZANU-PF engaged in its same old tricks. Whether he can translate those gains into a victory for the presidency remains to be seen. So does the Western world’s capacity to recognize the reality of the situation in Zimbabwe, and the lessons it holds for democracy under siege globally.

Robert Edwards

Robert is a writer and filmmaker. His films include Land of the Blind starring Ralph Fiennes and Donald Sutherland, and When I Live My Life Over Again (aka One More Time) starring Christopher Walken and Amber Heard, and the documentaries Sumo East and West and The Last Laugh, with Ferne Pearlstein. He was an infantry and intelligence officer in the US Army, and was a captain in the 82nd Airborne Division in Iraq during the Gulf War.