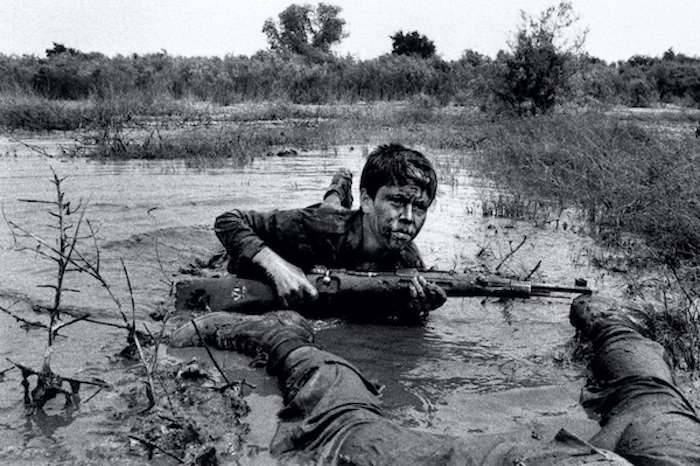

Young Iranian Basij fighters member of the paramilitary volunteers (Irregular Warfare) fight against Iraq’s

army in Susangerd front. Boy soldier of the Iran-Iraq war, Hassan “Jangju,” was killed in 1984 during

Operation Kheibar in Battle of the Marshes. Susangerd, Iran (March 1981) ©Alfred Yaghobzadeh

Translator’s Note: The shadow of the Iran-Iraq War looms large over Bijan Najdi’s work, and is particularly significant to the short story at hand, “The Darkness in the Boots.” Najdi’s story was published in 1994, just six years after the end of the conflict, which is often called the longest conventional land war of the 20th century. The most conservative estimates place the total number of casualties sustained by both sides from 1980 to 1988 at five hundred thousand people, with the lion’s share of the dead coming from the Iranian side. Many estimates place the total fatalities over a million. The entire demographic structure of Iranian society was rattled by the massive loss, and the generation that was coming into adulthood at that time—between thirteen and twenty-five years of age—is commonly known as the Burnt Generation (Nasl-e Sukhteh), referring to the loss of its future, of all its hopes and dreams.

It is on this Burnt Generation that Najdi’s story focuses, through the death of the young soldier Taher. Tragically, this generation was “burnt” on more than one level—on Saddam Hussein’s orders, Iraq repeatedly violated international law by dropping chemical weapons, such as nerve and blister agents, on Iranian soldiers and even civilians from the period 1983 to 1988. Additionally, some sources estimate as many as 144,000 children were orphaned during operations that the Islamic Republic of Iran calls “the Holy Defense” (defa’-e moqaddas) or “the Imposed War” (jang-e tahmili).

Najdi’s story explores the continuing fallout of the Iran-Iraq War long after its official conclusion, and illuminates the grievous injuries, deaths, and traumas that ripple outward through Iranian society down to the present day. In that sense, his work is a part of a well-established genre of war fiction and war cinema (sinema-ye jang), which has produced a staggering wave of art over the past three decades. By juxtaposing Taher in the body bag with another young boy named Taher, who happily plays at the riverside, Najdi highlights the random and senseless nature of Taher’s death and his father’s grief. In fact, throughout his collection Cheetahs That Have Run with Me, Najdi reuses the same handful of names for different characters, dampening their individuality. These characters quickly become ciphers, their experiences standing in for the experiences of everyday Iranians. Even the activity that Taher and his friends are involved in—diving for household objects at the bottom of the river in their imaginary underwater “home”—reflects generalized anxieties about the loss of the homeland and concerns over the integrity of places once assumed to be safe. The young boys attempt to construct a new “home” out of a collection of objects, reflecting the feelings of placelessness brought on by large-scale societal grief and displacement. Through his indirect but poignant allusions, Najdi has invited us to witness the aftermath of some of the darkest moments in Iranians’ collective history. Let’s not look away.

Iranian Basij fighters, members of the paramilitary volunteers (Irregular Warfare), on a Reconnaissance

Patrol mission as they march through the Marsh Farming land and toward Iraqi army positions.

Sayed Jaber, Khuzestan, Iran (Jan. 1981) ©Alfred Yaghobzadeh

Taher’s father had decided never to take off his black mourning clothes. One summer afternoon, though, the villagers saw him wearing an old blue shirt, headed for the river.

Had Taher’s father lived until autumn, it would’ve been four whole years since they buried that bag. Inside it, he caught a brief glimpse of charred and blackened pieces, burst eyes, and a face full of teeth. They told him that was Taher.

At the river, a few young boys were swimming. The day before, when Taher’s father was on his way home from one of his endless walks in the cemetery reading the gravestones—all the names and dates of which he never failed to recall effortlessly—he saw those same young boys playing in the water. The water carried the sounds of their laughter. It was unimaginable any one of them could be burned the way Taher had been. Father waved to the boys.

“Hi!” One of them called out. “Wait there one sec . . . ” He dove down into the water and came up with a moss-covered pot. “Look! You want it?”

Father was thin. Even if he dyed his hair and smiled with his mouth closed so no one would see his false teeth, all his squinting and straining to see the pot gave his age away.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“It’s a pot!”

The other kids were throwing an apple and swimming after it, making a ruckus.

“I found it down there.” He pointed down into the water.

Taher’s father said, “Okay, okay, I get it. Be careful not to drown down there. What’s your name?”

“Taher!”

And the bag was open again. Again, the crumpled skin, the burst eyes, those teeth . . .

Father’s shirt was damp with sweat. The frozen summer made his black shirt cling to his body. He turned around to see if there was anything behind him to lean against. A wall, a boulder—there was nothing. His hands came to the sand as he knelt down. Then he sat back, and he brought his fingers—which somehow felt miles away from his hands—towards his body and stuck them in his pants pockets. Let’s go then, old man. He pulled out a small bottle.

By the time he opened the bottle, pulled out the small red capsule of nitroglycerin and put it beneath his tongue, they had already buried Taher’s body once, dug it up out of the ground and buried it again. They’d covered it all with dirt, then shoveled it all to the side, pulled the body out of that dark pit, and buried him again . . .

That night, the river made so much noise on its way out to sea, smashing water against the rocks, that it startled the villagers awake. Father tossed and turned restlessly in bed until noon the next day. Around midday he ate a bite of food so he could smoke a cigarette. He never went over to the window. The curtains he left closed, and tried not to look at the picture frame on the shelf, which he had turned face down. Why hadn’t he taken that clay pot from Taher? He could have cleaned off the moss and put it next to the mirror, or on the shelf. He could have even invited Taher to his room to sit and talk once in a while. Can you even open your eyes at the bottom of a river? Isn’t it dark down there? Aren’t there plants? What about fish? From that vantage point, you could see a sky that definitely wasn’t blue anymore. Underwater, how would you know what day of the week it is? It must be pretty quiet. Down there, your ears don’t fill up with ants. Worms and lizards don’t crawl in your mouth. Under a water ceiling with water crown molding, in a room with water walls, nobody can tell when someone else is crying. That day, before Father really broke down crying, he left the house and the villagers saw him wearing his old blue shirt, headed for the river. The kids were swimming in the water. Taher floated on his back.

“Hello,” he said.

“Hi, how’re you?” Father said.

“How are you?” Taher replied.

“Eh, it’s so hot today,” Father said.

“Why don’t you strip down, then? The river belongs to everyone!”

“I’m old now. I can’t keep myself afloat.”

“You could roll up your pant legs though!”

Father took off his socks and shoes. He rolled his pants up over his knees. He sat on a round rock and put his feet in the water up to his ankles. The coolness of the water penetrated his very bones.

He struck his match two or three times to light a cigarette. “What did you do with that pot?”

“I put it back where it belongs.”

“Where it belongs?”

The other boys were swimming after an apple.

“There’s a house down there,” Taher said.

Smoke came out of Father’s mouth as he laughed, “A house? Down there?”

The kid who’d just made it to the apple yelled, “He’s telling the truth. Want me to bring up the pots?”

Before Father could answer, they all dove down deep. The apple floated on. Some bird momentarily cast a huge shadow over the river that looked like a bridge. Father watched the empty surface of the water with anxiety.

The river was quiet, like a nameless gravestone.

Father got up off the boulder and waded in up to his knees. Still unable to admit to himself how much he wanted to yell out, “Come up, you crazy kids!” He watched as, one by one, heads and shoulders emerged from the water.

They lifted their mouths up to the sky and sucked wind until their bones were full of air. And each one had a pot in his hand. Taher came up last of all. His hair clung to his forehead. He was covered by the water from the neck down, so you couldn’t see he was naked. He’d brought up with him a small window shutter from below. He waved it above his head.

“Look at this!”

“There’s a clock down there too, stuck to a piece of wood.”

“You can’t pry it off.”

“There’s lots of stuff.”

They went down again.

Broken pieces of a mirror with weeds stuck to the back, rusted spoons, small, black, crumpled trays—

Everyone had grown worried by the time Taher came up out of the water. His face was blue. He swam wearily and pulled out a pair of soldier’s boots. On the other side of the river, a sunflower drooped its head down toward the ground, and a poplar sagged, resting its branches on the cemetery wall.

The boots had no laces. They didn’t smell like feet, nor could you hear the sound of someone running inside them. They were cold. Full of mud. Father accepted them from Taher, like a tiny corpse. The kids were stretched out on the bank.

Taher was tall. His freshly-sprouted chest hairs were wet. His eyes were just as calm as the water, and just as blue.

“Put some clothes on, guys,” he said. “You’ll catch a cold. Somebody go get my clothes.”

“So what’s down there?” Father asked.

Taher, who was putting on his socks, said, “Nothing.”

“You mean there’s no house down there?”

“Nope.”

Everyone was looking at the pots, the shards of the mirror, the shutter, and the boots.

“We threw those things in the river ourselves, by the way,” Taher said. “See ya.”

“Wait, why?”

Taher and his friends walked away.

Father yelled, “Why, Taher? Taher! Why?”

He sat on that same rock until an hour after sunset and watched the water as it slowly turned muddy, then black. When he closed his eyes, he could hear the river flowing out into the sea. The boots had fallen over in the sand. Darkness enveloped his hand.

That same night, Father took the boots home and put them on the shelf.

He didn’t close the door. The curtains he left open.

Having spread out the sheets, he lay down and went to sleep with his eyes open. Just before or after midnight, the river flowed in through the half-open door, washing over Father and the boots.

A young Iranian boy hugs his uncle in Ahvaz cemetery during a funeral of his parents, brothers, and sisters—

all killed by Iraqi scud missiles in Ahvaz city. Iran (March 1981) ©Alfred Yaghobzadeh

Bijan Najdi (Author) / Michelle Quay (Translator)

Bijan (1941-1997), from Lahijan, Iran, was an experimental poet, fiction writer, and pioneer of postmodernism and surrealism in Iranian literature in the 1990s. He had a late-blooming but very successful literary career, and his collection Cheetahs That Have Run with Me (1994) generated considerable popular and critical acclaim for its fresh use of modern literary techniques in Persian. Najdi regularly presents his stories from the point of view of unusual characters—dolls, horses, a tattoo on a prisoner’s arm—in order to address events of historical and societal importance without arousing the ire of Iran’s strong governmental censors. He refers to this historical background obliquely, but it is critical to understanding how Iranian readers experience his work.

Michelle is currently Visiting Lecturer of Persian at Brown University. She holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge in Classical Persian Literature. Her literary translation work has appeared in such publications as Words Without Borders, Asymptote Journal, World Literature Today, Exchanges and others.

Alfred Yaghobzadeh (b. 1958) is an Iranian photographer whose career began in 1979 when the Iranian revolution interrupted his studies and sent him to the streets of the capital to photograph the tumultuous events that led to overthrowing. Distinguished for his choice of subjects that reflect the human cost of violence and conflict around the world, his images depict major world events such as the fighting between the Amal movement and Palestine in Sabra and Shatila camp Beirut in 1985, the civil war in Lebanon and Gaza, the Chechen battle of Grozny, and the Egyptian revolution in 2011. He has has received various prizes, including World Press Photo, The American Overseas Press Club, the NPPA Best of Photojournalism, and the Art and Worship World Prize (AWWP). His photographs have also been featured on the covers and pages of numerous international publications.