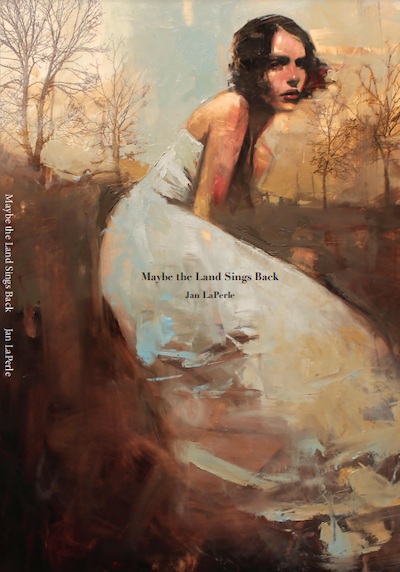

Maybe the Land Sings Back

By Jan LaPerle

Galileo Books, 2022

Jan LaPerle’s latest poetry collection, Maybe the Land Sings Back, begins and is interspersed with sheet music for Charles Wesley’s 1739 hymn “O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing.” The words are omitted, which is fitting, because LaPerle chooses to fill the following pages with new lyrics that seek out optimism in the recurring image of lamplit cafés amidst the dark conflicts of a soldier at home. In Maybe the Land Sings Back, LaPerle’s soldier-wife-mother struggles to reconcile her own agency as the husband she is divorcing confronts his own imminent death.

The first three poems in the collection provide a resonant grounding for the entire collection. In three swift blows, LaPerle walks us through the three major threads of the collection—motherhood, death, and divorce. In these opening moments, we see the speaker as a mother struggling to connect with her daughter, an estranged wife confused for her husband’s caretaker, and a divorcée navigating the felt absence of a now-missing partner. The attempt to preserve a sense of normalcy cannot survive the backdrop of the experience of global conflict. Human desire must take a backseat to family obligation, which must in turn take a backseat to the inherent tension between personal priorities and military service. Often, when the speaker begins to assert her need for art or sex, she finds herself thwarted by her own daily machinations and apologizing for even considering the act of intercourse.

It’s said there are no atheists in foxholes, and LaPerle’s soldier-speaker endures her domestic battlefield through prayer, spirituality, and an intimate recognition of her own soul. The clearest, most grounding moments in the collection arrive in the memories of early military life, as though the simplicity of soldiering allows for a reinforced social structure the murkiness of domesticity can never truly erase. The speaker’s daughter may provide domestic grounding in the first poem, where she plays hide-and-go-seek through dark, wooden halls, but the soldierly experience provides clarity and cohesion to tie the three disparate threads together.

It is in this recognition of the soldier identity that the collection finds its clearest cohesion but also its greatest flaws. “Yellow,” a poem centered on the loneliness caused by the speaker’s dying yellow chakra—the chakra commonly associated with rebirth, energy, and new beginnings—ignores the consequences of the speaker’s laughing outburst directed at a soldier with Tourette syndrome during formation and shifts to riff on the speaker’s loneliness—“as if we weren’t all so lonely, as if the sun wasn’t burning in our eyes.” In “Somewhere,” the poem focuses on the speaker’s motherly fear over recognizing her daughter’s youthful mortality by referencing “a soldier who once drove over a little girl the size of his own, to save himself, to save a hundred others.” In this moment, the speaker ignores the horrific consequences of what, in my combat experience, seems to be an easily avoidable act, to justify her own trepidation, something reflected in the soldier’s self-justification for killing a little girl. Both poems perpetuate what appears to be a lack of self-transparency on the part of the speaker. If this is intentional, then it allows for a roundness to the speaker’s character. However, the continued centering of the work on the speaker never allows for a satisfactory resolution that invokes depth in interpreting these moments as anything more than an American-centric view of recent conflicts.

In Maybe the Land Sings Back, LaPerle engages the truths of the soldier-wife-mother in lyric narration. Her speaker treads leaf-buried, lamplit roads to a flower-blooming life after the death of a husband she’d planned to divorce, ending with her sharing the buzzing light of a lamp in a hotel restaurant with other exhausted mothers. The music of her poems resonates in the ears of anyone who has spent time in both domestic and foreign battlefields. At its heart, this collection speaks to the grief inherent within the human soul, and how we all yearn to soak in the lamplight.

Clayton Bradshaw

Clayton is a queer, formerly homeless veteran who was a finalist for the 2021 Kinder-Crump Award for Short Fiction and is an alum of the Tin House Winter Workshop. He holds an MFA from Texas State University and is working towards a PhD at the University of Southern Mississippi. His work can be found in or is forthcoming from Fairy Tale Review; F(r)iction; Green Mountains Review; War, Literature, and the Arts; and elsewhere.