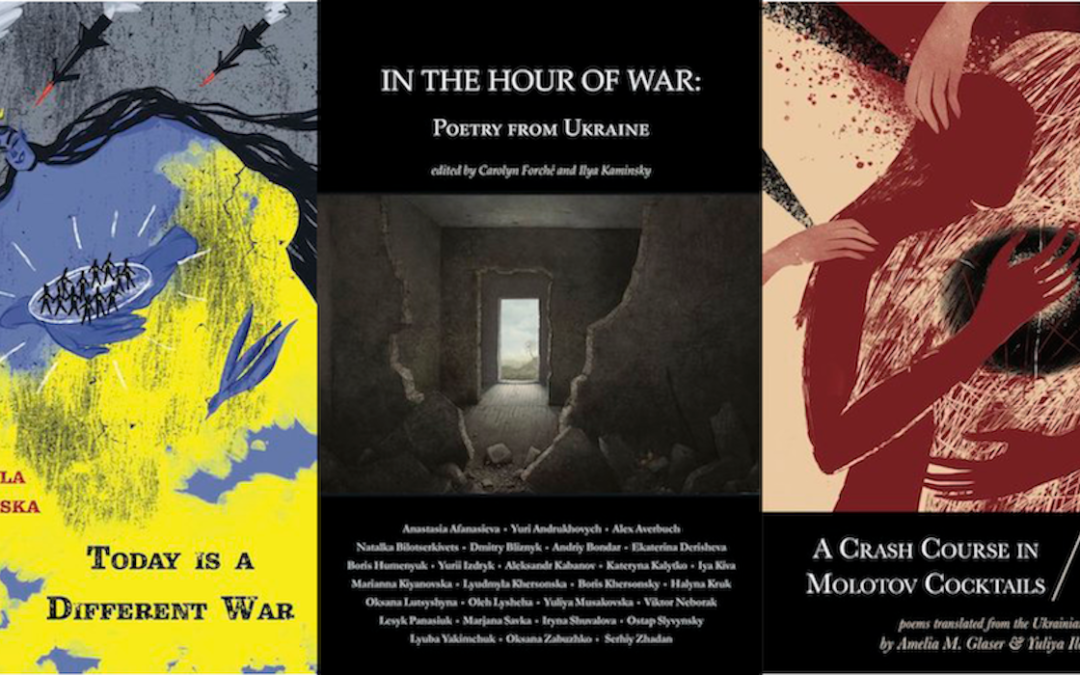

Today is a Different War

By Lyudmyla Khersonska, translations by Olga Livshin, Andrew Janco, Maya Chhabra, and Lev Fridman (Arrowsmith Press, 2023).

In the Hour of War: Poetry from Ukraine

Edited by Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky, with individual translators cited below (Arrowsmith Press, 2023).

A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails

by Halnya Kruk, co-translated by Amelia M. Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk (Arrowsmith Press, 2023).

✽ ✽ ✽

The three books of Ukrainian poetry Arrowsmith Press is releasing this spring constitute a significant contribution not only of poems but also of fuel for the debate on the relevance of poetry to the realities of war. The debate burns most brightly in A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails, by Halnya Kruk, but receives more indirect, and more conclusive, treatment in the indispensable anthology In the Hour of War: Poetry from Ukraine, edited by Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky. Today is a Different War, by Lyudmyla Khersonska, is the least germane of the three to such a debate.

The debate itself is problematic. Ekaterina Derisheva, in a poem from the anthology, provides a glimpse at the controversy:

while they sorted out who helped more

and in what language one should speak

where to publish one’s poems

what literary awards to compete for

while they offend and take offense

and write poems from abroad

the inhabitants hide from artillery fire

learn how to count again

one two three four five

What use is poetry during a mass emergency? Is poetic expression self-indulgent, scribbling and competing for literary prizes while Ukraine is under brutal attack? Or is writing poetry a mortal necessity, like going out to search for water while missiles are slamming into your town? Or a moral necessity, like heading to the churchyard to bury a child? Do poets at work outside Ukraine merit the scorn of those who’ve stayed? How does Ukrainian poetry in a time of such atrocity need to be transformed? Among the poets in these books, Kruk and her translators seem most preoccupied by such questions and have placed them front and center.

Kruk is a deservedly prominent voice. Her book is loaded with brave, gritty, complex, provocative poems. In the best of them, she concentrates on what she does most brilliantly, such as invoking the Judeo-Christian prophetic tradition in response to a violently transformed world, a psychic experience comparable to insanity or divine revelation. Halfway through the first poem, “bifurcation point,” she encounters another poet on the street in Kyiv at the start of the war. They embrace, both startled witnesses to the apocalypse, shocked into silence, but also conscious of a new reality and new responsibilities:

like the first Christians

who witnessed Christ’s miracles with their own eyes and had no idea

how to fathom it and how to make others believe and not mock them,

how not to twist or muddle things

This witnessing is, crucially, a shared condition. Kruk’s poems often seek a wider state of radically-collective self-recognition, as in the eschatological poem, “the history of mankind”:

we’ve never come so close to the world’s end

holding each other by the hand

never peered over the edge so casually, curious

how deep is it? how far down?

will the first soften the fall for the next?

Even the value of light is uncertain:

it settles there so evenly, like nothing’s happened

it’s refracted so sharply by water, by eyes

and other henceforth impenetrable surfaces

it’s reflected so desperately by metal

We often think of the apocalypse as a global event, the Four Horseman scorching the nations of earth, but most monstrously violent events remain stubbornly local. We suffer these events locally because violence is always local—my child, my home, my neighbors, my legs—and yet this limitation carries an understandable distortion: the end of time for my family and me is, well, the end of time. The annihilation of my family is the end of all meaning, at least temporarily. Kruk wants to show us the borders of her own apocalypse, how any sense of its limitations appears senseless, not only in a contemporary political realm, but in accordance with any notion of the meaning of history:

to see through the gaping hole

in a burned out high-rise

as Europe’s distant sun sets

i’ll have to rethink literary history

before I teach it to my students

Kruk harnesses her nation’s new moral authority to give voice to the desperate love and tenderness that people standing together at the edge feel for one another, for their collective despair and sense of responsibility, for their exquisite awareness of the light, of existence itself. She also allows plenty of room in the poems for anger, fear, bitterness, love, and hatred.

Nevertheless, it took me several readings to register the power of the book. Many of the translations have great passages, but fewer of them succeed as poems all the way through. From the beginning, certain missteps subverted my reading. The parentheses in first lines of the first poem, in “bifurcation point,” are laced with ironical commentary that comes off as winking at the audience:

in wartime Lviv, (they’ll write later)

there was a strong literary milieu,

most likely, they published as a group (like those modernists in “Mytusa”)

or gathered for readings (because what else would poets do in wartime!)

there were so many there:

the internally-displaced and the externally-dysfunctional

These gestures assume a cultural and intellectual intimacy with the reader that hasn’t been established yet, as if the reader also had reason to take delight in her condescension toward the Ukrainian “literary milieu.” Of course, the audience for these opening lines probably isn’t a reader like me, but rather the milieu in which Kruk herself holds a significant place. Publishing and holding poetry readings despite frightful repression has a strong tradition in some countries of the former Eastern Bloc, an expression of resistance and solidarity I’ve always admired. Does Kruk place herself above it?

Is she writing poetry to deride writing poetry? I could see how this incongruity could be funny or delicious with schadenfreude, like Dante encountering his rivals in hell. But, at least partially because the passage avoids any real specificity, pointing repeatedly to an uncharacterized “they” whose deficiencies I have no reason to acknowledge, the poem accomplishes no such thing.

I also spent too much time attempting to make sense of the co-translator Amelia Glaser’s introduction, where the clunky last line of the first poem—“the main thing is not to forget that none of this was about literature”—is cited both in the title of the introduction and as its last sentence. Glaser’s attempts to justify the centrality of this declaration are implausible. Her emphatic echoing of Kruk’s claim that the war calls for an “ethics of literature that bends formal poetic genres” will seem impossibly banal to American readers, for whom such a transformation began at least as early as 1855, with Leaves of Grass.

We learn in the introduction that had Kruk asserted pointedly at the Berlin Poetry Festival, in 2022, that “no metaphors work against an armed soldier” and “no poetry can save you from a tank.” These claims sound searing and impressive at first, but you quickly realize that both are only variations of the workaday fallacy known as the straw-man argument. Who, after all, had made such absurd claims to the contrary?

But in a larger sense, these assertions underestimate the role of language and its artifices. What usually stops an armed soldier? Answer: another motivated soldier. And how many soldiers throughout history have been motivated by anthems, flags, poems, tropes, and metaphors? Kruk’s insistence on a false disjunction between language and action is misguided. Like propaganda, art, literature, poetry, tropes, and metaphors—I’m thinking of all those images of Marianne, symbol of the French Republic, bare-breasted at the heart of the fray as she waves her tricolore—are neither innocent nor irrelevant. It’s untrue that Kruk’s book transcends such literary devices as metaphor. The poems sampled above are evidence enough. Such polemics distract from what is great and moving in her book.

I’m also troubled by the ending of the otherwise powerful poem “no war.” In another straw-man argument, the poem addresses an anonymous Russian war protestor Kruk appears to know of, maybe having seen her in the news, holding up a placard in a square or at a street corner. It’s not clear if the protestor is a real person or an imaginary composite. The poem says:

[…] the world got blown up into pre- and post-war

along the uneven fold in the “no war” sign,

which you’ll toss in the nearest trash can,

on your way home from the protest, Russian poet,

war kills with the hands of the indifferent

and even the hands of idle sympathizers.

It’s reasonable that Kruk should be frustrated by the asymmetry of surviving a war as compared to participating in a street protest, but she also seems to assume that such actions imply little risk in Putin’s Russia, which is plainly untrue. We learn nothing of the protestor’s motives. Was her eighteen-year-old forcibly conscripted? Has he already died in Donetsk Oblast? Maybe the humble gesture of holding up a cardboard sign is futile, but poets who require real-world heroism from others are on dicey terrain.

Glaser also asserts in the introduction that in shunning the “poetic features of language,” Kruk’s poems often sound “journalistic.” As “no war” blurs the edges of imagination and news, doesn’t Kruk bear another kind of ethical responsibility when she “sounds” journalistic? Is an antiwar protestor inside Putin’s Russia, unlike a soldier or a tank, only a literary device? You don’t have to be Ukrainian to feel the pain in these lines:

[…]what do we tell their mothers?

who will tell them the worst?

a person runs toward a bullet

with a wooden shield and a warm heart

head in a blood-filled ski helmet

shouting, “mama, i’m wearing a hat.”

My frustration with Today is a Different War, by Lyudmyla Khersonska, is more rudimentary. I usually admire books that skip the honorifics and polemics and go straight to the poems, but considering the complexity of this book’s cultural and political context and its remoteness to most Anglophone readers, it’s surprising to find no introduction or translators’ note. A stronger editorial standard or guiding principle might have helped. The first poem, “War. Day 1” (tr. Olga Livshin and Andrew Janco), about a young girl waking up to war, has a grammatical error in its second sentence:

She tumbled out of bed in her cheery pajamas,

ran across the chilly floor, like a blue sky, barefoot.

Is the floor like a blue sky? But grammatically I understand the meaning as her running “like a blue sky” across the floor. I love poetry that fractures syntax and I love this second version of the image, but as written the line reads as an error. The poem has a kind of naïve charm, especially in contrast to the complexity and occasional facetiousness of Kruk’s book, but its switching from the child’s third-person-limited perspective to an adult attitude subverts the characterization:

What is this red blob, flying outside the window?

What is this, so frightening? Flying over our heads

Towards such a peaceful morning

With such a demonic whistle?

Why are these clear glasses shaking, the clear soul, shaking,

Why is she trembling?

[…] “Is this war?” she asked the closed door,

barefoot in her cheery pajamas.

Rather than the character I hoped to encounter, the girl remains a figure in service of the poet’s rhetorical objective, a far less compelling result than the authentic child’s experience I was led to expect might have been. This want of individuality in the characterizations is a problem throughout Today is a Different War, the result being that few of the poems are as affecting as what we read daily in the news.

Ukrainian is not one of the languages I can read, and so I can’t comment on the specifics of the translations, though these rarely instill confidence. A distracting lack of concision and clarity, and an excess of editorializing, undermine the text throughout. In its struggling to rhyme, one poem, “Russian Invader, Who’s Forgotten All Chivalry” (tr. Maya Chhabra), is both a warning and a call to arms, but has all the qualities of dubiously punctuated doggerel:

Russian invader, who’s forgotten all chivalry,

Fear female revenge and female conspiracy,

Fear Ukrainian girls, Molotov cocktails in hand,

Fear our women, above all in this strange foreign land.

I suspect the poem is meant to be funny and inspiring, but it’s neither. The lack of artistry becomes cruder, more unfortunate, more banal by the end:

To turn your uncleansed life into an eternal torment of shame

We ignored Solovyov and read—Kafka and Kierkegaard, by name.

Remember, we’ll forgive nothing, you scumbags, so flee your fate.

We’re painting our nails now. Get out of here—before it’s too late.

Yet here and there lines or sentences penetrate the noise in Today is a Different War to sound the notes of a more substantial art. This simple statement in “In a Different Country” (tr. Lev Fridman), is unforgettable:

long ago the cat learned to hear mice in the walls

And then, there’s this, from “War. Day 10” (tr. Maya Chhabra):

and they gathered up all the books they’d written

and piled them high in heaps on the windowsill

and pressed them to the window […]

and the books held fast, defending the room,

books against missiles, against shrapnel,

against glass

It’s feasible that stacking books against a window can help reduce the danger of a blast if the blast is far enough away, I suppose, or, conversely, that doing so is as pointless as trying to stop a tank with a poem. But underlying the practical element, what’s moving in this effort is its futile dignity, the stacking of books a metaphor for the collective character of the people who participate in this action as an answer to a shattering loneliness in the face of a violent death, as if the act of joining in could in some way save them.

Another sequence comes from the first stanza of “Where, She Asks, Are My Irises” (tr. Olga Livshin and Andrew Janco):

yeah, the purple ones, but especially

the yellow ones, have you seen them?

they were tall, with their little tongues sticking out,

their leaves were sharp and strong,

they were so tall, so peaceful.

maybe you’ve seen them?

The nationalistic symbolism in these colors might seem problematic, but the clarity of the passage is a relief from the chaos and editorializing in the writing that surrounds it. Of course, it helps to keep in mind the suffering and courage of Ukraine’s current moment in reading this excerpt—the sense of loss seems simple and true. I see both love and horror in those “sharp and strong leaves,” those “little tongues sticking out.”

And I was glad to come across Khersonska again, beautifully represented in In the Hour of War: Poetry from Ukraine, the anthology edited by Forché and Kaminsky. Here, Khersonska’s poem, “Keeping House” (tr. Diane Seuss with Oksana Maksymchuk), reminds us how domestic housecleaning can also be an expression of trauma, a quotidian sublimation of loss that obfuscates its finality. The figure of the housecleaner is at once intimate enemy and cruel truth teller:

Every time he leaves the house, she cleans. Tosses out his old papers.

Why does he need all these

timeworn books?

[…] He circles back home. Back

home? Everything is missing!

His papers, his books. His sack of maps.

He wants to know:

Did you throw away my black folder?

Yes. I’m sorry. It’s gone.

Her broomstick in one hand. Wet rag in the other. Her lips hold back a yawn.

The awfulness of her work becomes more and more clear:

He crawls through a spill of old photos on the floor.

[…] Where are my parents? Dear God,

My parents! You’re going mad, she says.

Come to the table. Your soup is growing cold. Get off the floor. Your

parents are dead, Shlema.

There are too many breathtaking poems in the anthology to sample here. The poets speak directly for themselves through very skilled translations, by many translators, providing a level of clarity and precision that defies their distance from us. The poems remind us that in some way, this or any war has an infinite number of sides and each civilian, combatant, and refugee is a hive of intentions, loyalties, and sorrows.

Some motifs reoccur throughout: family, homes, gardens, trees, God, and of course literature and language. The poems often focus on metaphysical matters, or on the elusive edges of metaphysical realms and the emptiness behind disconnectedness. To quote again from Retivov’s translation of “in the ‘war’ mode” by Derisheva:

while it is being decided which language

will be the leading one in literature

they go bonkers on the other end of the line

trying to reach God by phone

or anyone for that matter for hours

hello hello hello

The mystery, vulnerability, and sentience of trees resounds, as in the poem “Not To Wake Her Up” by Serhiy Zhadan, (tr. Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps), where the trees reach

toward those places,

where our atmosphere breaks off

and where nothingness begins,

almost reaching that point where twilight appears

Hate is ever-present, as in “[Between hate & love]” by Ostap Slyvynksy (tr. Katie Ferris and Ilya Kaminsky):

Clarity is so instant that not everyone remembers to shut their eyes,

Many lie down, blinded, in the gardens in the outskirts.

Those who remain see their lips as if by honey sealed,

repeating words of love only, and hate.

“Our faces, tossed about this land,” by Lesyk Panasiuk (tr. Katie Ferris and Ilya Kaminsky), where Russian soldiers are compared to worms, is haunted by the dehumanization inherent in war. This comparison of humans to vermin has a grim history in war and genocide, and while the impulse may be comprehensible given the vivid viciousness of the Russian soldiers described in the poem, given the necessity of dehumanization in military indoctrination—how else do you annihilate a city or shoot down a terrified, stumbling teenager who looks just like your little brother?—the poet seems to want and not want to get away with it.

Worms are, after all, not only “vermin” but the reputed “guardians of the soil.” How do you distinguish a Russian worm from a Ukrainian worm? The “black soil” reference below suggests not only Russian nationalist pride—a variation of the notorious German “blood-and-soil” symbolism—but also what might be said to organically join Russia and Ukraine, both nations straddled by a vast expanse of chernozem which comprises some of the world’s richest agricultural land. Gaining full control of this region is often cited as a core justification for the invasion.

Panasiuk’s poem is as much a dismantling of the long history of Ukrainian-Russian cultural and political intimacy as of the poet’s conception of himself, losing his ability to see himself in his enemy:

Russian soldiers drop from the sky clinging to parachutes—

to the corners

of our lips

their fingers

hook.

These parachutes, torn, are no

longer our cheeks

our noses, our teeth:

In the mirror

I do not see my face.

They are dropping, they are climbing down the stairs

of the sky.

Our faces, our tornswollen

faces our clattering the earth faces, dirty, our

faces tossed among the shards of this day.

Near the end of the poem, I read the word “yes” in the phrase “yes like worms” as the poet’s acknowledgment of the moral disaster in this symbolism. It’s as if the poet aches to address this hazard, but it simply cannot be the right moment, as the emotion is overpowering. The violence and grief remain too extreme:

Russian soldiers are like worms yes like worms they are crawling out from their

black soil of Russia

to die in the puddles of tears on this Ukrainian street

[…] they drop here clinging

to parachutes

of our faces

But no laughter

is heard

No laughter on the lips of our faces which are tossed about in the backyards

Any debate about the legitimacy of poetry in wartime is given only occasional reference in this illuminating and beautifully edited anthology. It’s the poems themselves that prove how crucial poetry remains in our historical moment. In my mind, these poems settle the debate. To anyone who cares to glimpse behind the news reports and photojournalism, which often feel so opaque, our impulse for understanding and compassion frustrated and diverted into voyeurism, this anthology is a chance to listen more deeply, more intimately to the pain and complexity many brilliant writers would have us hear about.

I cannot recommend Today is a Different War, by Lyudmyla Khersonska, except to say it provides a glimpse at what may be a more substantial art. I look forward to a more effective representation of her work. A Crash Course in Molotov Cocktails, by Halnya Kruk, is complex, aggravating, essential, and I expect it will get ample attention, despite or maybe because of its incongruities, its defensiveness, its straining towards polemic. As for the anthology, In the Hour of War: Poetry from Ukraine, edited by Carolyn Forché and Ilya Kaminsky, I know no better guide for a reader who seeks a deeper understanding of the incomprehensible in its current European iteration.

Peter Brown

Peter is an artist, writer, and translator. He has published two books of poetry in translation, including a French translation (with co-translators Caroline Talpe and Emmanuel Merle) of the poems of David Ferry, Qui est là? (La Rumeur Libre, 2018) and Elsewhere on Earth, (Guernica Editions, 2014), a collection by the French poet Emmanuel Merle. A collection of short stories, A Bright Soothing Noise (UNT Press, 2010), won the Katherine Anne Porter Prize.