A sign for a restaurant at the Del Rio port of entry.

Photo: Jenn Budd.

Few Americans understand the policies that make up the immigration deterrence operations of the US Border Patrol. These mandates are often confusing and can change drastically from one administration to the next, or even within a single legislative term. Furthermore, the media surrounding deterrence policies is heavily based in pro-deterrence, anti-immigrant rhetoric that criminalizes asylum seekers, while news coverage in general consists of Border Patrol talking points that neither match the experiences of the asylum seekers or those living along the southern border.

To understand what deterrence policies are and their actual effects requires lived experience, gut-wrenching self- reflection, and un-embellished storytelling. I’ve experienced the southern border as a Border Patrol agent and as an immigrant rights activist. I knew the border before deterrence policies and after. I’ve witnessed their consequences and the propaganda the Border Patrol and US government use to continue selling the policies as “the only way.” For nearly thirty years, I’ve participated in, watched, and studied these policies and have come to the conclusion that they do not deter anyone from crossing illegally. Instead, these policies have, among other effects, killed tens of thousands of people, separated thousands of families, and criminalized innumerable asylum seekers. These policies violate human rights under the guise of national security with both Republican and Democratic congresses and presidencies being responsible. It’s my belief that these deterrence policies will one day be listed in the history books alongside the US Native genocides, slavery, Japanese Internment, and other US atrocities.

The personal essays included in this series all deal with my experiences related to these policies.

—Jenn Budd

Part 1: “Deterrence Policies of the US Border Patrol”

Part 2: “Outdoor Encampments”

*Names have been changed to protect those involved.

In September of 2021, local Haitian-American leaders and members of Alliance San Diego asked me to join them in their trip to the Border Patrol’s Open Air Detention Site (OADS) in Del Rio, Texas. They asked because Texas authorities had begun enforcing federal immigration laws with a flare of old southern brutality, and aside from being a migrant rights activist, I knew both the Border Patrol as a former agent and the ways of southern cops and sundown towns as I grew up in Alabama. My role would be limited to providing them with guidance regarding the Border Patrol’s culture and protocols and any safety issues that might arise from their operations.

At first, I politely declined. While an agent, I’d never encountered any Haitian asylum seekers nor any OADS. But also, and maybe more to the point, my time in the agency left me with serious PTSD from enforcing brutal laws, and witnessing families being held outdoors in lean-tos made from cardboard or sticks and blankets would undoubtedly lead me to another episode of depression—brought on by the shame of once wearing the green uniform—that took days, or sometimes weeks, from which to recover. Every time someone sent me a picture of a dead migrant, or when a female agent called to talk about how she’d been sexually assaulted or harassed by other agents, or like the time I received a video of an agent putting a gun in his mouth threatening to end it all, my mind required extended self care and healing to get past all of the flashbacks, the bad dreams, the self loathing.

I could not sleep that night, though, as I kept remembering one of the most important lessons I’ve learned in doing migrant rights work: that listening to the trauma of migrants and subsequently helping people understand the agency’s cruelty often opens doors to healing, not just for myself and agents but for migrants too. My personal trauma is deeply tied to the migrants. Too many years of making excuses for having worn that uniform and enforcing brutality that went against my morals and values left me hating myself. My time in the agency left me with opinions bound in racist ideology that were drilled into me in the Border Patrol academy.

More than anything, though, I felt obligated. It was Alliance San Diego that had helped me walk into the pain I carried for my actions in the agency and helped me see that this was the only way to heal. They helped me understand my time as an agent and my responsibilities as a human being. This was the key to curbing my self hatred.

✤

On the long flight to San Antonio, I spoke with John and Louis. Both are local southern California Haitian-American leaders—a preacher and a lawyer, respectively. They and other Haitian-American delegates were coming from all over the country to see what the Border Patrol was doing to their fellow countrymen. They were to bear witness so that this moment of inhumanity would be documented and not lost to the constant retelling of history that is so common with the Border Patrol.

Louis informed me that, contrary to what the press was reporting, the agents from the Del Rio Sector had been holding Haitians there for months. He started getting calls for legal representation from Haitians held under the bridge as far back as July 2021. Now, in September, the camp had grown from 9,000 to 14,000. Publicly, the Border Patrol said they were overwhelmed by so many migrants suddenly showing up at one port of entry. John asked if this scene was intentionally created by the agency.

Though I did not know first hand, I told them it was not likely that they were caught off guard by such a large number of migrants. Contrary to what the Border Patrol says publicly, they do have a decent control over the border. During the Clinton and then George W. Bush administrations, we were lucky if we apprehended 40-50 percent of those people crossing between the ports. Today, that percentage is normally around 80 percent or higher. Additionally, today’s Border Patrol uses informants and has its agents and National Guard soldiers secretly deployed within both the migrant caravans and the shelters south of the border. They also employ continuous monitoring of their WhatsApp communications. This is why it isn’t possible for such a large group to travel through the countries south of our border without Mexican and American law enforcement knowing it.

After landing in San Antonio, we rented three cars to drive west an hour and a half to our hotel in Uvalde. Del Rio was still ninety minutes away but all the rooms there had been taken by the federal government for what they called the “Haitian crisis.” We were eager to find the Haitian migrants that the media claimed were everywhere, so we dropped our bags in our rooms and drove the final ninety minutes to the border. John and Louis piled into one car while I jumped in with those from Alliance San Diego: Sarah, Maria, and Javier.

I reminded everyone that we were no longer in California and to be careful about their driving as the local cops were working with the Border Patrol. Had they stopped us, the Haitian-Americans would have their citizenship questioned and could likely find themselves sitting in custody for months trying to prove their legal right to exist in our country. They could have even been unjustly deported. John laughed as he sped off not taking my warning seriously.

The closer we got to the Del Rio border, the more cops we saw. The Texas DPS (Department of Public Safety), Del Rio Police Department, and Val Verde Sheriff’s Department were everywhere. We were about fifteen minutes out from Del Rio when I phoned John in the car ahead of us to pull into the next gas station along the small two-lane Highway 90. He had been speeding at times as he enjoyed the company of his fellow countryman, and I feared they had not been paying attention.

“Have you noticed all the cops?” I asked at the gas station. He could see the stress on my face. “I need you to trust me when I say these guys are not fucking around. I have witnessed and participated in the brutality of the Border Patrol.” John promised to slow down.

Operationally, I could see that the local cops and the Border Patrol had complete control over the area. As we drove the last few miles into Del Rio, we noticed the Texas DPS vehicles parked in the grass facing the highway. Their headlights aimed right into every car or truck passing. The better to see skin color, I thought, knowing that federal law allows the Border Patrol but not the Texas DPS to racially profile within a hundred miles of any land or water border. Each half mile or so, there was another vehicle. Flashbacks invaded my thoughts of myself in that green uniform sitting in a Border Patrol sedan on the highway watching cars pass by, doing the same thing these cops were doing.

But Del Rio was quiet that first night. We saw no migrants, no asylum seekers. The bus station was empty. The federal port of entry was closed thanks to Texas Governor Greg Abbott staging Texas DPS officers on the road with their cars blocking all traffic going north or south. The large group of Haitians being held in the open air camp were trapped between the Rio Grande River and a tall metal fence built by the state of Texas.

Haitians were being held in Border Patrol custody between this fence and the Rio Grande river.

Photo by Jenn Budd (September 2021)

The next day, I was stuck at the hotel for an interview via Zoom. I spent most of the day coordinating with team members and observing federal officials in Uvalde. As I stared out at the flat lands surrounding our hotel, I noted how dense the brush was in this area. My mind went where it always does, and I wondered how many dead migrants were hidden in that thick brush that extended from Uvalde to the border in Del Rio. Memories of dead bodies encountered in Campo, CA, and Indio, CA, flashed in my brain like an old movie, and I closed my eyes tightly each time as I shook my head trying to make them stop. I found myself looking for the signs that migrants had passed through: pushed down vegetation, disturbed dirt that showed varying colors of moisture, a brightly colored piece of fabric stuck to a bush with stickers or thorns. When on the border, I look for them, for the bodies. I cannot help it.

As night started to fall on the second night of our stay, the traffic on the highway in Uvalde picked up. Chartered buses, immigration buses, and school buses were all headed down to Del Rio. I saw large vans with DHS (Department of Homeland Security) plates, rented vans, and trucks pulling into our hotel. Those in my group wondered aloud if the government was getting ready for the Haitian delegates. We expected agents to clean up the camp, have water and food contrary to what we had seen in photos taken before we arrived. To me, though, the charter buses suggested they were trying to empty the camp before we arrived with delegates.

By the following morning, all the government and rented vehicles were gone. Sources I had in the small town of Acuña, Mexico—just south of the OADS—had confirmed my fears that Border Patrol agents were quickly forcing the Haitian families from under the bridge into every conveyance they could find. Haitian-American delegates were coming from New York and Miami to witness the squalid scene for themselves and had been coordinating with CBP thinking that the agency was being honest with them.

In my opinion, this rush to get rid of the Haitian families was because DHS, CBP, and the Border Patrol did not want the Haitian-American delegates to see the horrible conditions the migrants were being held in. They did not want those delegates to get on television to recount what they had witnessed. They did not want the truth to be told. So they erased it. The US government disappeared over ten thousand people in three days with no explanation, no investigation, and no comment from the media about how this could happen.

On our third and last day, our delegation from San Diego was joined by another delegation from Miami, and even though we knew they were disappearing people, even though we worried about our safety and what the Border Patrol and local cops had in store for us, even though CBP had warned the delegates to be out of Del Rio by sundown for their own safety, we still went. I closed my eyes and took a deep breath allowing myself to feel the fear I had for my fellow travelers and myself. On the way to a migrant shelter in Del Rio, I called my wife to tell her that I loved her.

When it was time for the Miami delegation to walk out to the OADS with the chief of the Del Rio Sector’s Border Patrol, I decided did not to go with them. Instead, I stayed back, waiting outside of the second gate and watched from afar. My presence there would’ve only antagonized the Border Patrol. Besides, there was nothing left to witness but bulldozers and workers scraping and piling up the makeshift tents and shelters the families had made. It was a final slap in the delegates’ faces by CBP and the Border Patrol. The cruelty was increased when the Border Patrol refused to state what was done with the Haitian asylum seekers. Later, we learned they were dispersed out to other sectors to be processed and deported back to Haiti.

By the time we were done in Del Rio, it was almost dark. “CBP said we need to get out of town before dark,” I said, reminding our group. Javier jumped into a car with a friend, and before I realized it, they had left. Maria was already on her way back to Uvalde with the Miami delegation in her car. “I hope they don’t get stopped. We were supposed to always be in sight of each other,” I commented to Sarah as I sat in the passenger seat.

Halfway to Uvalde, we got a call from Javier that they were being tailed by Texas DPS. The troopers followed them so close it caused them to panic and turn onto a smaller road. “Never get off the main road,” I said. “Get back to the highway!” Every time they pulled over, the cop pulled over yet never used his emergency lights or got out of his vehicle. This was an intimidation tactic meant to create fear. For reasons unknown, the trooper eventually pulled off and left them but not before terrorizing them.

Next came the call from Maria. She and her car full of Miami Haitian-American delegates were pulled over several miles ahead of us. The DPS officer claimed her tail light was out. She replied that it was a rental and that she was not aware it was broken. After ordering her to turn her lights back on and exit the vehicle to see the problem, the trooper told her that it was now miraculously working. He still issued her a warning for her tail lights not working, even though they were working. My father’s words about some towns in Alabama echoed in my head: “If you’re Black or Brown, best be out of town by sundown.”

On the face of it, if you are not a person of color or if you have not experienced sundown towns, you might think this is no big deal. From my experience, I knew these tactics were meant to strike fear into the hearts and minds of our crew who were all of color. It was to tell them that they were being watched. The fear in Javier and Maria’s voices was raw and painful. In law enforcement, they say there are no coincidences. Indeed, we were being targeted. There was no other reason for their actions since we weren’t speeding or committing any traffic violations. Sarah and I were the only car not harassed that night. This was likely because of my white face and blond hair and her presenting as white, though she is white and Asian. Our back seat Haitian-American passengers were slumped over sound asleep and not visible.

Our crew refused to stay one more night in Uvalde because they were afraid for their lives. Coordinating by cell phone, we agreed to gather our things and get back to San Antonio that night before flying out the next day. Our luggage was packed and we all stood in the hotel’s parking lot as I set out the plan. “We have to stay together this time. If one of us gets stopped, we all stop. Do not get out of the car. Document every . . . ” my voice trailed off as we all looked up to see what the noise was. A police helicopter was flying about thirty feet above us. Its rotary blades blew debris and trash all around. I yelled for everyone to meet at the gas station across the street to gas up and looked up one last time to see a cop with an assault rifle in his hands staring back at us, smiling.

It was the longest hour and a half drive back to San Antonio that I’ve ever made. I could feel the fear in my colleagues and it shamefully reminded me of how migrants used to fear me because of my green uniform and what I once represented. No one from my group will talk about our trip to Del Rio to this day.

The truth that most Americans do not know or want to admit is that the US has been holding migrants and asylum seekers in inhumane, inhospitable Open Air Detention Sites (OADS) for years. This new policy of holding asylum seekers outdoors does not appear to be a written public policy, and the agency claims these camps do not officially exist much the same way they claimed the policy for separating children did not exist. Whether the policies are written down or not, these open air camps are being used by Border Patrol as deterrence tactics. Agents believe if migrants and asylum seekers experience how horrible the conditions are, they will return to Mexico. The camps are an escalation of the deterrence policies I used to enforce, and they will kill migrants just the same.

To truly understand how these camps emerged, you must know how the agency changed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Although the agency and its policies are rooted in white supremacist ideology created by white segregationists and eugenicists of the 1920s, the Border Patrol has been indoctrinating its agents into the criminalization of asylum seekers and migrants at a level that did not exist prior to 9/11. While those who committed the terrorist attacks gained access to the US through legal ports of entry, they lied on their immigration documents and exploited the system. This monumental failure of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, which Border Patrol was under at the time, was taken advantage of by hard line anti-immigrant groups, political leaders, and the Border Patrol to expand their power and influence without accountability. This expansion is why the agency is more brutal than before 9/11 and is directly tied to the rise in white nationalism today.

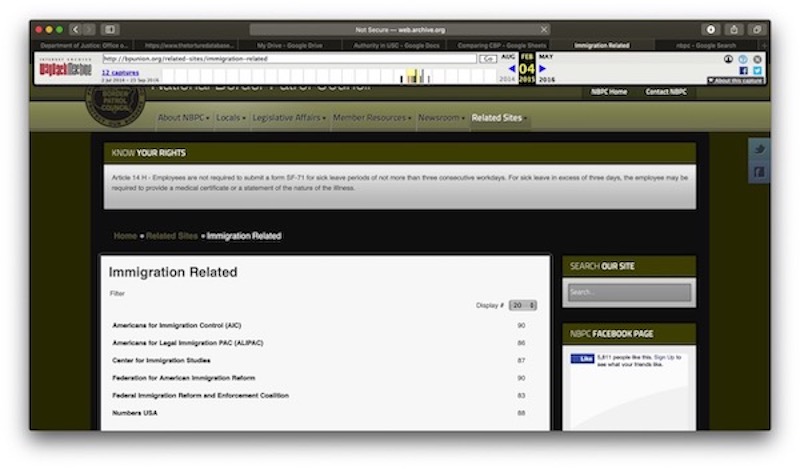

Asylum seekers were not called “invaders” in the agency until after 9/11 when the Border Patrol aligned itself with anti-immigrant hate groups like the Federation of Americans for Immigration Reform (FAIR). Post 9/11, FAIR and other anti-immigrant groups claimed they were only interested in promoting legal immigration, but as the Southern Poverty Law Center has documented, these groups consist of eugenicists and anti-immigrant proponents who have strong ties to white supremacist organizations. It is through the Border Patrol Union that agents were introduced to these anti-immigrant hate groups and where they got many of their post 9/11 ideas like separating children from their asylum seeking parents and Open Air Detention Sites.

National Border Patrol Council (BP Union) spread anti-immigrant hate to agents through its website but removed this page once the SPLC named these groups hate groups.

The earliest I can find any documentation on Border Patrol’s use of these camps was in 2019 when outdoor cages were used to hold migrants apprehended by the Tucson Sector Border Patrol. These enclosures that were positioned in the harsh Sonoran Desert between Naco and Douglas, Arizona, wouldn’t have been acceptable to house animals as they had no shade, sanitation, food, or water. Yet migrants had to wait in the desert sun during the day or in freezing night temperatures until transportation vans came to pick them up. The cages were removed in 2020 only after a filmmaker and professional photographer by the name of John Kurc discovered them while filming the Trump administration’s ecological destruction for their border wall and questioned Tucson Sector staff about them. This article is the first documentation of these cages. It is not known if any persons were injured or died by being held in them.

US Border Patrol cage used to hold migrants in the hot Sonoran Desert.

Photo by John Kurc.

In June of 2019, the press finally caught on when Robert Moore wrote in Texas Monthly about an Open Air Detention Site used at a Border Patrol facility in El Paso, Texas. Asylum seekers were held in this “dog kennel” for weeks. Again, there were no showers, but there were a few portable toilets. Families were forced to sit outside in the hot Texas sun and rain. When they needed to sleep, they had to sleep on the ground in the dirt and mud. Once again, the Border Patrol publicly claimed they were overwhelmed. A few months after the article was published, I was able to travel to El Paso to witness the scene for myself, but the agency had already removed everyone after the camp had become public knowledge.

Not to be out done, in 2021 the Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector held thousands of migrant families under the Anzalduas International Bridge in the Rio Grande Valley. Like other Border Patrol Open Air Detention Sites, this one had little food or water. There were no medical personnel on site, no legal assistance, no shelter, and little sanitation. The Border Patrol stated this site was called a TOPS or Temporary Outdoor Processing Site.

In May of 2023, Trump’s scam of using a 1940s health policy under Title 42 to shutter the asylum system was coming to an end. Asylum seekers who could not get appointments with the new CBP One app and were turned away stated to me that they were told by CBP officers to walk west of the San Ysidro port of entry and cross the border irregularly under the first wall to be processed by the Border Patrol. This put families in between two border walls and trapped them there. Within a week, the area between the walls then became another Border Patrol Open Air Detention Site.

This camp in San Ysidro, CA, is where I spent two days volunteering and speaking with asylum seeking families while handing them food, water, and hygiene products through the steel wall bollards. While some were told by CBP to cross irregularly, I witnessed others being brought into this area by Border Patrol agents themselves. Contrary to the agency’s statements in the press and to Congress, these migrants were not allowed to leave. They were heavily guarded by Border Patrol and ICE agents armed with assault rifles. They also wore colorful paper bracelets issued to them by the Border Patrol. The colors coordinated with the day they entered the camp.

May 2023 end of Title 42 in San Diego, CA.

Photos by Jenn Budd and Dorothy Mantooth.

In June of 2019, the press finally caught on when Robert Moore wrote in Texas Monthly about an Open Air Detention Site used at a Border Patrol facility in El Paso, Texas. Asylum seekers were held in this “dog kennel” for weeks. Again, there were no showers, but there were a few portable toilets. Families were forced to sit outside in the hot Texas sun and rain. When they needed to sleep, they had to sleep on the ground in the dirt and mud. Once again, the Border Patrol publicly claimed they were overwhelmed. A few months after the article was published, I was able to travel to El Paso to witness the scene for myself, but the agency had already removed everyone after the camp had become public knowledge.

Not to be out done, in 2021 the Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Sector held thousands of migrant families under the Anzalduas International Bridge in the Rio Grande Valley. Like other Border Patrol Open Air Detention Sites, this one had little food or water. There were no medical personnel on site, no legal assistance, no shelter, and little sanitation. The Border Patrol stated this site was called a TOPS or Temporary Outdoor Processing Site.

In May of 2023, Trump’s scam of using a 1940s health policy under Title 42 to shutter the asylum system was coming to an end. Asylum seekers who could not get appointments with the new CBP One app and were turned away stated to me that they were told by CBP officers to walk west of the San Ysidro port of entry and cross the border irregularly under the first wall to be processed by the Border Patrol. This put families in between two border walls and trapped them there. Within a week, the area between the walls then became another Border Patrol Open Air Detention Site.

This camp in San Ysidro, CA, is where I spent two days volunteering and speaking with asylum seeking families while handing them food, water, and hygiene products through the steel wall bollards. While some were told by CBP to cross irregularly, I witnessed others being brought into this area by Border Patrol agents themselves. Contrary to the agency’s statements in the press and to Congress, these migrants were not allowed to leave. They were heavily guarded by Border Patrol and ICE agents armed with assault rifles. They also wore colorful paper bracelets issued to them by the Border Patrol. The colors coordinated with the day they entered the camp.

Migrant shelter in the Jacumba, CA, Border Patrol outdoor encampment.

Photo by James Stout (September 2023)

Once the Border Patrol decided to make the San Diego open air camps permanent, the agency changed tactics and began using the nonprofits and their volunteers to provide food, water, and medical supplies. Volunteers brought tents and built structures paid for by donations, only to have the agents tear them down and trash everything when the volunteers were out purchasing food and water for the migrants. The next day, volunteers would bring in more tents and build again. All supplies and services were provided and paid for by these groups and not the Border Patrol or CBP. From my experience working out there, I do not doubt that many migrants would have died had it not been for the activists, volunteers, and groups like Al Otro Lado, Universidad Popular, and American Friend Services Committee feeding and providing water. Many of those held in these camps are children and babies.

The only difference between the first open air camps and the ones in San Diego is that those in San Diego have never shut down. They are still open and the Border Patrol continues to state that they are not camps and that they do not officially exist. This means the agency continues to refuse to provide food, little water, shelter or medical assistance.

On October 11, 2023, the first migrant to die in a US Border Patrol Open Air Detention Site was reported. While officials have not given any reason or cause for the twenty-nine year old’s death, Border Patrol Agent A. Martiniez of the Imperial Beach Station stated to me the following day that he felt bad for the family. He claimed he was ordered to place the deceased woman’s family in a van and deliver them to processing. They were not allowed to stay or see their loved one as her body now belonged to the medical examiner. It was another way our immigration policies separated another family permanently.

No one in the press nor in the government seems willing to talk about the fact that these Open Air Detention Sites keep popping up. The Border Patrol would like everyone to think they are spontaneous and uncontrollable, yet they easily take back control whenever they choose and they are able to continually design and build other Open Air Detention Sites to hold people.

But now, these “unofficial camps” are staying. It is my belief that since the press is not covering the sites as aggressively as they did in the past, since the public did not express much outrage at the death of a young woman, the Biden Administration has no cause to take them down and treat asylum seekers any more humanely. Even under a Democrat president, investigations are rarely done and the ones that are tend to be rather incomplete and full of outright lies by the CBP and the Border Patrol. The most recent detention inspections report from the DHS failed to even mention or inspect the Open Air Detention Sites in San Diego.

✤

It has been a few years since that trip to Del Rio, Texas, with the Haitian-Americans. I still have nightmares that often resemble what happened to Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner in Mississippi in 1964. My inability to write about it for so long is directly tied to the level of trauma I witnessed my friends enduring, but it is also deeper than that. It is only through writing and rewriting this piece that I have unlocked this deep uncertainty and pain.

I believe there is a part of me that still wants to believe in American exceptionalism, that concept that our institutions are somehow better or more virtuous than those of other countries. I long for it simply because it was easier for me when I believed it. To witness my fellow countrymen holding asylum seeking families (in those conditions and laughing about it) forever destroyed those beliefs. This is what prevented me from saying yes immediately, and what has gnawed at my conscience since. Add to that our history of enslaving and brutalizing Black peoples and that those fellow countrymen were wearing the same uniform I once did . . . it was the death knell of my belief in American exceptionalism. There is nothing I can say to justify the Border Patrol’s use of these Open Air Detention Sites. Nothing.

And so, I no longer lie awake at night wondering if I should go when asked to witness. Flashbacks and memories are small inconveniences for my past actions. Witnessing and sharing what is being done in the name of national security is my duty, one that I swore an oath to uphold. That oath was about protecting the US from foreign and domestic harm, and I believe our immigration policies are walking the country into self-inflicted harm that we have yet to understand.

Jenn Budd

Jenn was a Senior Patrol Agent with the U.S. Border Patrol in San Diego and an intelligence agent at San Diego Sector Headquarters from 1995 to 2001 when she resigned in protest due to the rampant corruption and brutality she witnessed on a daily basis. Her memoir, Against the Wall, was a finalist in the 2023 Triangle Publisher’s Randy Shilts Award and received an honorable mention in the L.A. Book Festival in 2023. She is often interviewed for outlets such as The New York Times, Newsweek, The Guardian, Washington Post, NPR, Telemundo, MSNBC, and many more. She has recently started a new website to document and track Border Patrol brutality called Border Patrol Watch.