Take these seeds and put them in your pockets so at least sunflowers

will grow when you all lie down here.

— A Ukrainian citizen

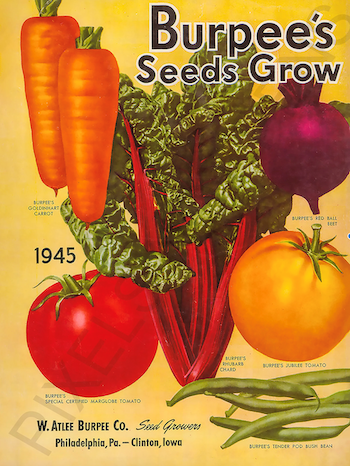

My grandfather worked as a seed breeder and farmer at Fordhook Farm in Southeastern Pennsylvania. Sometime in the late 1930s, he crossed the Tangerine tomato with the Rutgers tomato, producing the Jubilee, a delicious orange beefsteak-type that became a Burpee Seeds classic.

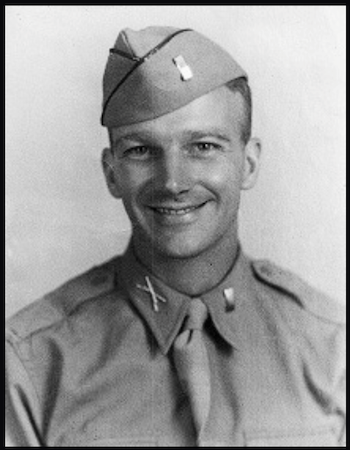

I discovered this tidbit of family lore recently, researching my grandfather’s service in World War II. I had already heard the story of how one year as a prank, he crowned the family Christmas tree with an “experimental onion” in lieu of the traditional star. The word “experimental” mystified me until a photograph of my grandfather at Fordhook surfaced.

A young man of about thirty, my mother’s father is on bent knee in a field of cut grass: Tan and wearing a white t-shirt, light-colored trousers and white sneakers, he looks more like a tennis player than a farmer. He’s not a particularly large man, and though lean, his arms are strong and muscular. His sandy-colored, thick, wavy hair is brushed up and full on the top of his head. On the camera-facing side of his face, a hint of sideburns, or perhaps they’re his version of the five o’clock shadow.

He’s looking at one of the paper tags attached to harvested squash. An older farmer sits nearby, pipe in mouth, pen in hand, and appears to be recording field trial data. The vegetables surrounding the two men are mostly crook-necked and have a bumpy surface, like barnacles on a ship’s hull. In the background, more of the same variety of squash are piled into crates, waiting to be evaluated.

So, this was “experimental” farming: Crossing the desired traits from one plant with those of another, such as disease-resistance and taste, to produce the perfect variety.

Better seeds are planted. Now watered. Now sunned. Now harvested.

* * *

Tomatoes are self-propagating and contain both male and female attributes; the seed breeder designates a father flower and a mother flower for the cross. The mother flower is emasculated, leaving the pistil. Using small forceps or tweezers, the breeder firmly—but gently—applies pollen taken from the father flower to the pistil of the mother. The process is repeated over two or three days. The seed breeder waits patiently for the swell of the first fruit, the ovary, which contains the seeds for the new life form.

* * *

The Victory Gardens movement of the First World War took deeper root during the Second World War, as part of a U.S. government public relations campaign. Promotional posters featured American families dressed in red, white, and blue farming attire, wearing bright, can-do expressions and armed with rakes, shovels, hoes, and dirt-filled wheelbarrows. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt established a White House War Garden. In 1943, Americans planted twenty-two million gardens. The go-to source for seeds to help in the fight against Hitler and his tyranny was the Burpee Seeds mail order catalog.

It was a time of food shortages and rationing. Burpee Seeds CEO, David Burpee, wrote in the 1943 catalogue, “The food shortage is just beginning to be felt, but in other countries people are starving. We must send even larger quantities of food to our Allies and to our own men in the Armed Forces.”

As a farmer and the father of two small children, my grandfather could have taken deferment. His parents, perhaps his wife also, begged him not to enlist. But shortly after the United States entered war, my grandfather entered basic training at Fort Benning, joining Company A, 12th Regiment, 4th Infantry. Assigned the rank of second lieutenant, he shipped out to Europe in the late spring of 1943.

He carried a small bible my grandmother had given him. In one of his letters, he mused about the 91st Psalm. He asked her if she agreed that “No evil shall befall one who dwells in the house of the lord” was a “pretty fine promise.”

The Jubilee made the cover of Burpee’s 1945 catalogue and was praised for its golden orange color, low acidity, and high vitamin C content. In his message to subscribers, CEO David Burpee applauded their patriotism. The company would later send my grandmother a check for $500 for my grandfather’s “creative work.”

In early fall 1944, in advance of my mother’s fourth birthday in October, my grandfather drew a picture of a birthday cake with four candles.

“Honey, I won’t be there to help you eat your cake, but at your party please remember that daddy is thinking about you and . . . if you watch closely, I’ll blow really hard from over here, and you’ll see one of the candles go out.”

In the same letter, he mentioned another letter on its way in which he inserted blue flowers he picked from the English countryside, because they reminded him of some flowers they’d picked back home. “Maybe we’ll go again, next summer.”

In late November 1944, during one of the coldest winters on record and the longest battle in U.S. Army history, my grandfather was killed in Germany’s Hurtgen Forest. Pine and fir trees towered 150 feet, perfect targets for enemy fire because they explode nicely into deadly shrapnel.

So, this was and is war: An experimental contracted battle for not-so-new varieties of democracy, resistance, power, and tyranny.

Just ask the parents of the six-year-old girl wearing a pair of unicorn pajamas, who died on an operating table of a Mariupol hospital. The man whose wife and unborn child were killed. The forty-one-year-old man whose older brother, a father of two small children, had his head blown off while going to buy food. Ask the thousands more who have fallen, the millions who have already fled to Poland, and yet to flee if they’re lucky.

It’s spring in Eastern Europe; a season unlike any other and exactly like the last one.

* * *

In the autumn of 1944, two months before the 4th Infantry arrived at Hurtgen, my grandfather wrote to my grandmother about some trees he had watched change color in England. How different they seemed from the changing season and trees back home, he observed. “Looking at them in clumps, they appeared similar, but when I look at them individually, they seem very different after all.” For some odd reason, I imagine the trees looking back him—a mutual acknowledgement of nature’s cycles and the inevitability of loss.

I try not to think about the death forest.

When I can’t help myself, though, I imagine him still breathing and looking up. The canopy of pine and fir is intact: A dwelling of towering trees yet to be bombed.

* * *

I think about all the fatherless summers and about my grandmother who never stopped longing for her husband but found some solace in the collective, post-war promise of “never again.” Twenty-six days into Putin’s assault on a country where billions of sunflowers still turn their faces to the light, I have nothing more to offer her than this memory crossed with wishful thinking: It is summertime in Pennsylvania. The slight-pine scent of the vines and the lazy buzz of insects fill the air. Your beloved has done the painstaking work of impregnating the parent flowers, waiting, and finally harvesting, drying, and planting their seeds.

The dirt at his feet is freshly watered, or perhaps baking silently. He’s proud that his Jubilee has resisted the black cankers that other varieties had no chance of fighting. He feels the sun on his sideburns, the same sun that makes a tomato red, yellow, and orange.

Lee Doyle

Leonore’s (Lee’s) work has appeared in Nostos, Creative Dreamers Magazine and other publications. Her debut novel, The Love We All Wait For, received the award for “Best Novel” at the East of Eden Writers Conference. A native of California, Lee now lives in Portland, Oregon.